Even years later, when hot water flows freely from the tap, you still take faster showers than you need to. You still feel a little guilty lingering. Somewhere deep down, part of you believes hot water is something you’re borrowing, not something you own.

Poverty leaves fingerprints on the way you think. On how you move through the world. On the decisions you make even when no one is watching.

People call it frugality. Sometimes they even admire it. They say things like, *“You’re so good with money,”* without realizing that what they’re praising is a trauma response. It’s not discipline—it’s memory. It’s remembering what happens when there isn’t enough.

Growing up poor also messes with your relationship to security. You don’t trust it. You can be safe for years and still feel like you’re one missed paycheck away from everything unraveling. Stability feels suspicious. When things are going well, you wait for the catch. You don’t fully relax. You don’t fully believe it will last.

“You’ll be fine,” they say, as if fine is the same as healed.

But fine doesn’t mean untouched.

Fine doesn’t mean you don’t still flinch when unexpected expenses show up. It doesn’t mean you don’t feel a spike of anxiety when your bank app takes a second too long to load. It doesn’t mean you don’t instinctively check prices—even when you don’t need to.

It definitely doesn’t mean you don’t carry shame.

That’s one of the quietest, most persistent souvenirs of growing up poor: shame without a clear origin point. Shame about your teeth. Your clothes. Your accent. The way you order at restaurants. The way you hesitate before saying yes to things that cost money. The way you learned to say “I’m not hungry” when you were.

You learn early how to disappear. How to not ask. How to not want too much. Wanting feels dangerous when resources are limited. Wanting can make you a burden.

And even when you “make it out,” the past doesn’t stay neatly behind you. It leaks into your present in small, surprising ways.

Like how you still keep extra food stocked, just in case.

Like how you struggle to spend money on yourself but have no problem helping others.

Like how luxury makes you uncomfortable—not because you don’t like it, but because you don’t feel like it’s meant for you.

There’s also grief. Real grief, even if no one ever taught you to name it.

Grief for the version of yourself who grew up too fast.

Grief for the ease you never had.

Grief for the parents who tried and still fell short—not because they didn’t care, but because the system was stacked against them in ways that love alone couldn’t fix.

Growing up poor teaches you that effort and outcome are not always connected. You can work hard and still lose. You can do everything right and still come up short. That lesson makes you resilient, sure—but it also makes you cynical in a way that’s hard to unlearn.

You stop believing in simple narratives about success. You don’t buy into the idea that anyone can make it if they just try hard enough. You’ve seen too much. You know how many people are working themselves into the ground just to stay afloat.

And maybe that’s why “you’ll be fine” feels so dismissive.

Yes, you survived. Yes, you adapted. But adaptation isn’t free. It reshapes you. It rewires your nervous system. It teaches you to live on alert, to plan for absence, to expect loss.

Some people grow up assuming the world will catch them if they fall. Others grow up knowing the ground is hard and learning how to brace for impact.

Those are two very different starting points, and they don’t magically converge just because time passes.

If you grew up poor, you might find yourself constantly proving your worth—not just at work, but in relationships. You overgive. You overperform. You apologize for existing. You feel like you have to earn your place everywhere you go.

Rest feels undeserved. Ease feels suspicious. Joy feels fragile.

And yet, there’s also a quiet strength that comes from it. A deep competence. A creativity that knows how to make something out of nothing. A sensitivity to other people’s struggles that isn’t theoretical—it’s lived.

You notice when someone’s shoes are worn thin. You hear what’s not being said when someone says they’re “fine.” You know how much dignity matters when resources are scarce, because you’ve felt how easily it can be stripped away.

Still, none of that cancels out the truth: some experiences imprint themselves permanently.

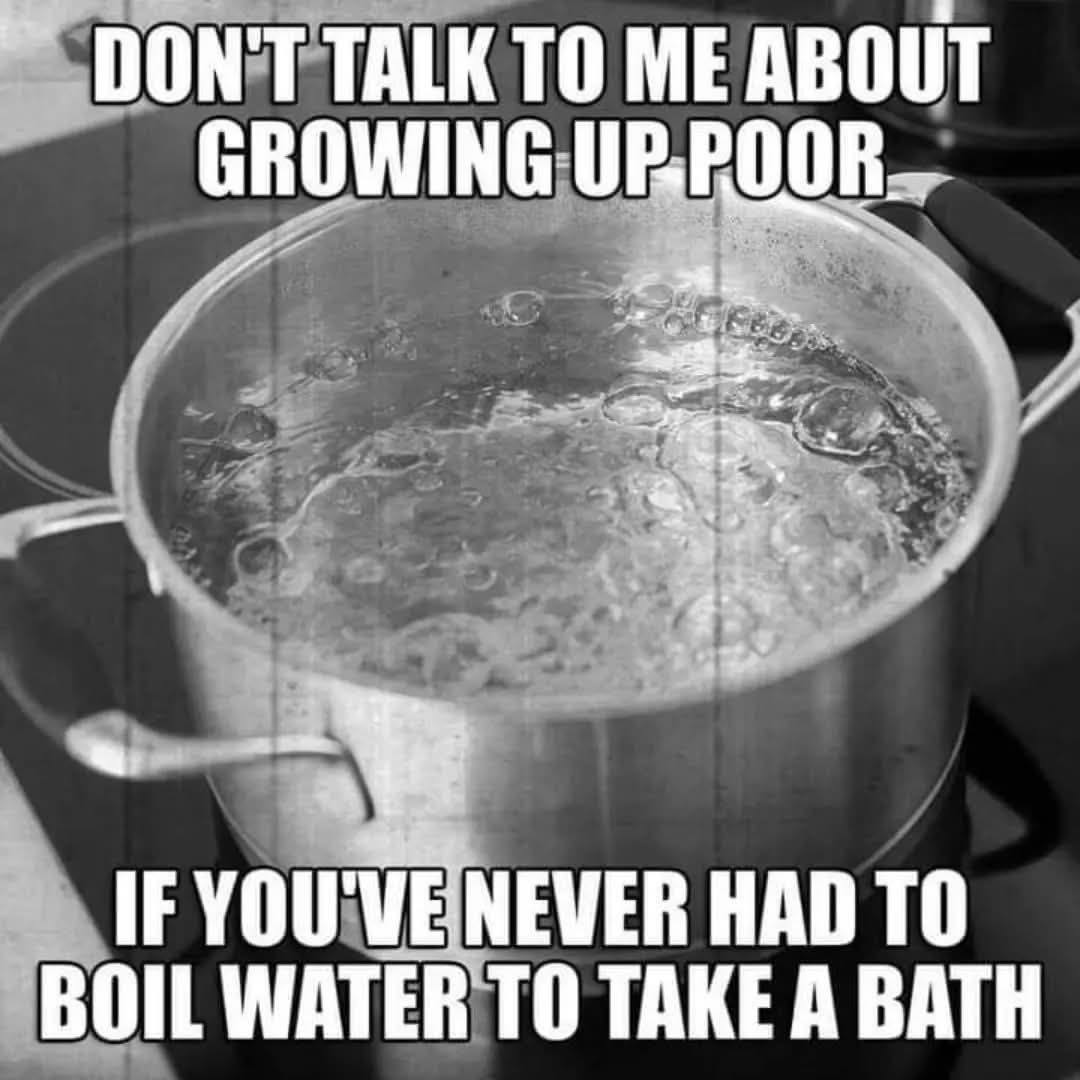

Boiling water for a bath isn’t just a memory—it’s a symbol. Of all the ways you learned to compensate. Of all the ways you learned to make do. Of all the ways you learned that comfort is conditional and temporary.

So when people say, “You’ll be fine,” maybe what they mean is, “You’ll survive.”

And yes. You did.

But survival isn’t the same as forgetting. It isn’t the same as being unaffected. It isn’t the same as not carrying pieces of that life with you into this one.

Growing up poor doesn’t always leave visible scars. Sometimes it leaves habits. Reflexes. Silences. A certain way of holding yourself in the world.

And if you know, you know.

You can be fine—and still remember the cold.